Just imagine, you open the door of your home and your entire living room is covered with a metre of sand. Before the summer of 2022, this was the harsh reality for hundreds of coastal residents in Togo and Benin. Calculations by the World Bank, among others, show that coastal erosion amounts to more than 2.5 metres a year in Togo and as much as 4 metres in Benin. Locally, even more serious cases of up to 10 metres a year have been observed. In addition, along the entire West African coast, the number of flash floods due to increasingly turbulent weather, which in turn is caused by climate change, is rising drastically, affecting half a million people annually.

A total of some 200,000 people live on the coast of Togo and Benin. Most of them by far depend on fishing and, to a lesser extent, on arable farming. With long nets attached to their boats, fishermen sail out to reel them back in a few hundred metres away in the South Atlantic, hoping for a catch. But can the thousands of fishermen in the coastal region continue to do that work, and support themselves and their families, when their homes are being devoured by the rising seawater? No. In other words, coastal erosion has catastrophic consequences for their way of life and their survival in the places where they have lived and traded for generations.

Sand motor

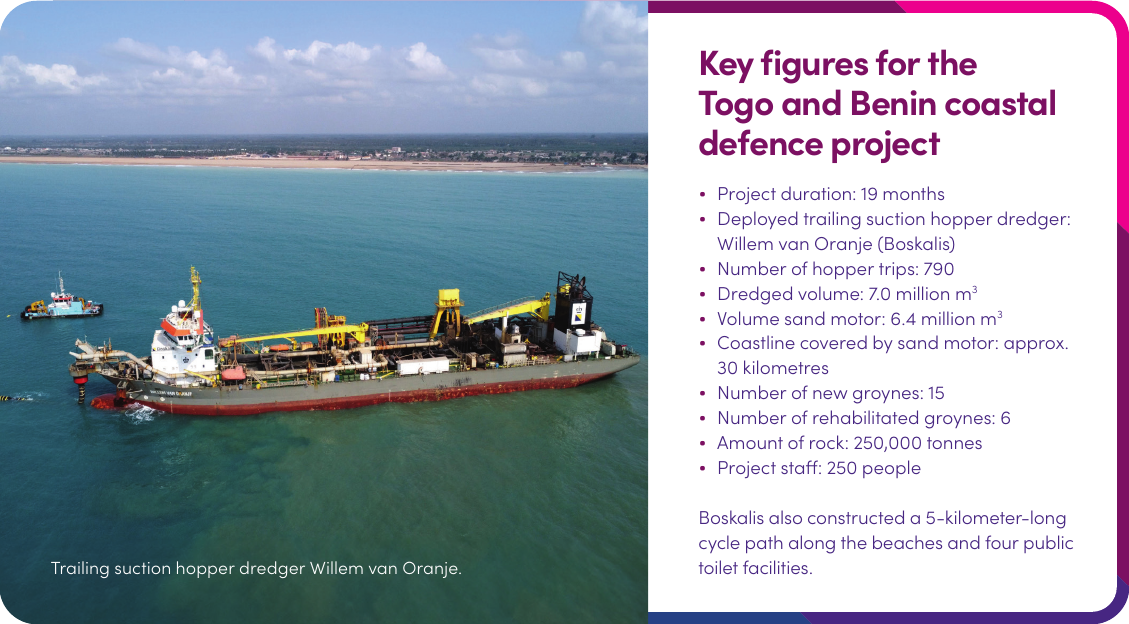

The dredging work that has been executed will preserve living conditions on a part of the Togolese and Benin coasts for decades to come. Even though that may sound unlikely, this is an accurate picture. With the construction of 15 new groynes, and the reinforcement of another six that were already in place, the project means that all the sand on the beach will be kept in place. In addition, the rock structures built at right angles to the beach mean that erosion will be less severe than in recent years.

Furthermore, with the help of Boskalis’ trailing suction hopper dredger Willem van Oranje, the beaches have been raised with more than a million cubic metres of sand. Not only that, a sand motor consisting of 6.4 million cubic metres of sand has been created on the Benin side of the border, and that sand will be spread along the coastline by the currents in a natural way. The Willem van Oranje made exactly 790 trips from the offshore sand borrow area to the coast for this nature- based solution.

Boskalis was awarded the contract by the governments of Togo and Benin, with funding coming from the World Bank. Discussions with Boskalis convinced both West African countries of the potential of the proposed dredging solution. Because strengthening this section of the coast by implementing a dredging solution means that coastal residents can rest assured that their homes will be protected for the next 50 years. Since only part of the beach was closed off during the work at any given time, and completed sections were immediately returned to the community, the social impact of the far-reaching work on the coast was limited. And the regular base for fishing, and therefore economic activity, was kept intact throughout the operation.